Overcoming the Critical Inner Voices in Your Head

Published on 14th November, 2017 by Muhammad Haikal Bin Jamil

"I am not good enough”.

“He’s smarter than you”.

"Are you sure you are doing the right thing?”

All of us have a critic within us. It is the voice which nudges us to view the world with a negative or unsafe filter. This critical voice can influence our behaviour - threatening us with social ridicule during a presentation, questions our words and actions during a first date, and reminds us of our past failures in life.

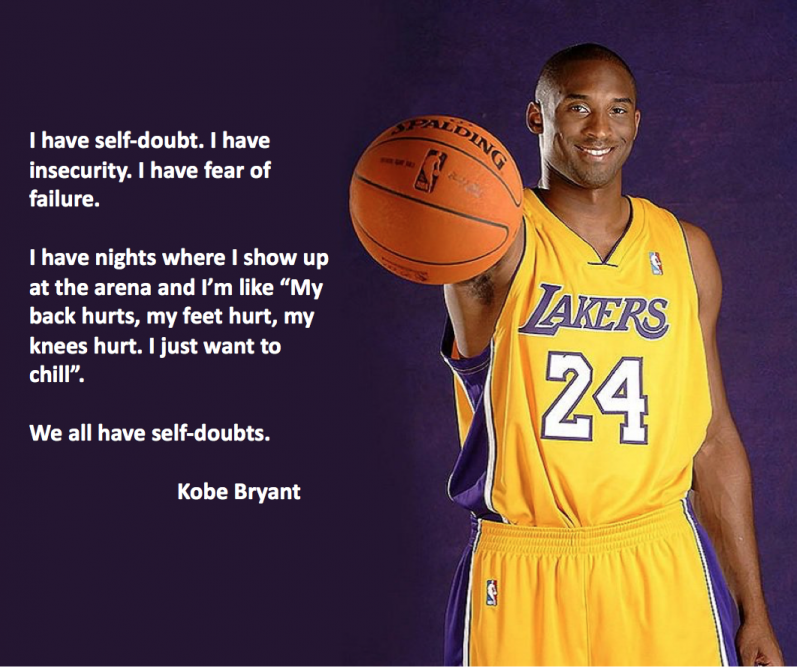

As a clinical psychologist, I have noticed that the critical inner voice is often an obstacle faced by most people- whether it is a client suffering from a mental health issue, such as depression or psychosis, an athlete suffering from a spell of low confidence, or an entrepreneur evaluating the likelihood that an idea will be a successful one. Even the most successful individuals are not spared by their critical inner voice, such Kobe Bryant, arguably one of the best basketball players in the history of NBA.

Why do I have a critical inner voice

i) A brain wired for survival

In the developed society that we live in, we can easily obtain food from a restaurant. Our homes protect us from storms and provide us with shelter. Modern medicine also enables us to be vaccinated from diseases such as measles and smallpox. This wasn’t the case many generations ago. The ancient humans have to be alert to potential dangers, such as the presence of predators in the environment and being able to identify poisonous fruits that should not be eaten, in order to survive.

Although the world has progressed much in the past century, it takes thousands of years for the brain to evolve. In fact, the structure of the human brain is relatively similar to that of other animals. The innermost regions of our brain, also the oldest part of our brain, continue to perform the functions of survival of our forefathers, including regulating our breathing, responding to perceived danger, and processing emotional experiences. The risk of being a predator’s next meal is much lower now, but as a result of millions of years of evolution, our brain is hardwired to naturally alert us to the dangers in the environment. In the current world, these include the risk of social ridicule, financial instability, and even the likelihood of not getting enough likes for our posts on social media!

ii) Past experiences

Exposure to threats, such as family violence, neglect, and controlling behaviour, are associated with higher levels of self-critical thoughts and emotions. How others relate to us, especially at a younger age, is associated with how we relate to ourselves. For example, a person who is often criticized by his parents for not performing according to their high expectations in school, may have develop a critical inner voice reminding him, “I am not good enough” or “I am a disapointment”.

Research has shown separate brain pathways exist in response to threats and positive experiences (Gilbert et al., 2006). Individuals who are exposed to negative events at a young age are at risk of overstimulating the threat system in their brain and increasing their sensitivity to threats. This gives rise to frequent and a more “powerful” critical inner voice, warning them of likelihood of getting hurt, controlled or rejected. The lack of activation of the positive affect system at a young age also hinders the maturity of this brain pathway. As a result, the individual may also face difficulties in reassuring themselves in difficult times and have less memories to dispel the criticisms brought about by the critical voices.

4 steps to overcoming with my critical inner voice

Step 1: Identify negative thought patterns

Recognize what your critical inner voice is telling you. Although the inner voice may be sending us many messages- from what we should or should not say or do, to how others may perceive us negatively, there is a common pattern or a common message underlying our inner voice. Psychologists often refer to this as one’s core belief(s).

For example, I recall seeing a male client several years ago, who wanted to address his anger outbursts. He had been physically abusive towards his girlfriend, and decided to seek help after injuring her after a quarrel. Although the issue may be minor, a disagreement may result in him shouting at his girlfriend and hitting her. I learnt that he was not from Singapore and grew up in a rough neighbourhood. He was subjected to constant bullying from his peers, which only stopped after he got angry, fought back, and injured one of the bullies. He has since developed the core belief that “People will hurt me if I show weakness”. While this cognition kept him safe until he finished school, he continued to be wary of people disrespecting him, and would respond with anger and violence.

Being aware of the thought patterns of your inner voice reduces the power that it has in influencing your behaviour. It is the beginning of being able to choose how you respond in a given situation, and break away from your usual behaviour.

Step 2: Distance yourself from the thought

Your inner voice seldom speak the truth. However, what the inner voice say is often unchallenged and you probably do not notice how it influences our behaviour. It should be pointed out the critical inner voice tends to magnify the negative aspects of the situation, and leads us to feel worse than we actually should. For example, a local study highlighted that undergraduates in Singapore with critical inner voices which facilitate negative self-view, such as “I do not measure up to my peers” and “I need luck to do well”, are more likely to develop clinical levels of test anxiety while preparing for their examinations (Wong, 2008).

As shown above, although our inner voices are just words (sometimes supplemented with images) in our heads, it has much power over us when it is left unchecked. One simple way of separating yourself from your inner voice is recognizing that the inner voice is simply a thought in your head, and not a fact (Harris, 2011). For example, when your inner voice tells you, “It’s your fault”, modify it to “I notice that I am having a thought that this is my fault”. This gives a sense of separation from the thought instead of enticing us to believe it and negatively influence our behaviour.

Step 3: Practice self-compassion

Self-compassion can be defined as relating to oneself with kindness and empathy. Individuals who were exposed to unloving or abusive environments may find self-compassion a strange concept. They have almost always been blamed for whatever issues that exist and they always get called out for their mistakes.

Adopting a self-compassionate approach to your critical voices involves understanding the reason why the inner voice is saying what it is saying, and exploring less hostile ways of feelings and thinking. The key is developing an insight into the responses of the inner voice as a safety behaviour/strategy, and establish a more empathetic alternative. For example, Mary's critical inner voice often tells her that she doesn't deserve to be loved, leading her to choose to stay in an abusive relationship as she fears that she may not find another partner. After reflecting with self-compassion, she may develop the insight, “I am used to thinking I don’t deserved to be loved, which has negatively influenced my relationship with others. Now, I am aware that this served to protect me from my critical parents in the past. These thoughts are understandable, but are not reflections that I deserved to be abused by others”.

Part of being self-compassionate is also about being aware that the critical inner voice is a norm, and not something to fear or to be ashamed of. I believe almost everyone, if not everyone, has a critical inner voice. Those who do not have a critical inner voice, or are unaware of it, are likely to be narcissistic individuals (which is another problem altogether).

Step 4: Alter self-limiting behavior patterns

You have learnt how to reduce the power of the critical inner voice in the first three steps. However, the only way to gain power over your inner voice is to get into action and keep working until you get the results that you want. You might need to evaluate, and adjust your strategy along the way. You may also need to equip yourself with new skills and practise it. But that is fine.

The inner voice is privy to your deepest fears, and is pretty efficient in generating excuses too. Allowing it to rattle your confidence and motivation could leave you stuck, or even lead you away from your goals. However, once you start acting and begin taking control of the situation, you will find that the influence of the inner voice begins to diminish as you become more confident. As highlighted by Harris (2011), the actions of confidence precede the feelings of confident. If you want to achieve something, you have to do the work first before you can start feeling confident. Waiting for your inner voice to tell you that you are ready or to assure you that you can achieve your goal before you start doing anything is unlikely to happen.

Recall the quote by Kobe Bryant above. Imagine if Kobe had waited for his inner voice to tell him that he will score lots of points and go on to be a great player before he decides to play a game. Would he have won 5 NBA titles and be an 18-time All-star player? His achievements were the result of his choice to keep pushing on despite the critical inner voice. This doesn't mean that Kobe's critical inner voice stopped after he achieved a certain level of success. However, the power that it has on his emotions and behaviour would have certainly diminished.

References.

Gilbert, P., Baldwin, M. W., Irons, C., Baccus, J. R., & Palmer, M. (2006). Self-criticism and self-warmth: An imagery study exploring their relation to depression. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 20(2), 183.

Harris, R. (2011). The Confidence Gap: A Guide to Overcoming Fear and Self-doubt. Shambhala Publications.

Wong, S. S. (2008). The relations of cognitive triad, dysfunctional attitudes, automatic thoughts, and irrational beliefs with test anxiety. Current Psychology, 27(3), 177-191.